By Zoe Fanzo

When Joshua Tillman was a child growing up in Rockville, Maryland, his evangelical parents allowed him to purchase music, as long as he could prove it to be produced by a “Christian Artist.” Tillman purchased Bob Dylan’s born-again-christian-era album, Slow Train Coming, successfully proving him to be a spiritual musician. Years later, Joshua Tillman would follow in Dylan’s footsteps, becoming a folk icon of the twenty-first century, best known by his stage name, Father John Misty. Misty has been called the “Lady Gaga of folk music” and performed on Saturday Night Live in March of 2017. Though folk music is often compartmentalized by mainstream music-listeners as conservative, traditional, and simple, American folk music actually has a rich history of serving as a mouthpiece for radical political discourse, and bolsters a vast dichotomy of musicians and perspectives. For Dylan and Misty, folk music became an artistic outlet in their respective eras of political turmoil. American folk icon Bob Dylan rose to fame with the debut of his second album in 1963, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Five decades later, American folk still serves as a means of political commentary. Father John Misty, sings of the dangers of the overtly religious American right and the rapidly rising culture of anti-intellectualism on his 2017 album, Pure Comedy. Honing in on Dylan’s 1963 song “Masters of War” and Misty’s 2017 song “Pure Comedy,” one can detect that the artists both use folk music to reject political leadership during eras of political turmoil. While the artists share a genre, in further examination of their diverging tones and differing perspectives on religion, the two prove to be less similar than they do at first glance. Essentially, folk music proves to be a complicated genre, incapable of compartmentalization.

Bob Dylan and Father John Misty both utilize folk music to reject political leadership during their respective eras of political turmoil, proving folk music to be capable of radical discourse. Similar criticisms can be seen in their works, including jabs at cowardly leaders and condemnation of greed-driven actions; in essence, they attempt political mudslinging through song. Bob Dylan critiques the Cold War military-industrial complex in his 1963 song “Masters of War.” Dylan refers to unnamed corporate leaders who profit from war as being cowardly and illusive, heatedly singing, “I just want you to know / I can see through your masks.” Dylan condemns these leaders for investing in war, raging:

Let me ask you one question

Is your money that good?

Will it buy you forgiveness

Do you think that it could?

I think you will find

When your death takes its toll

All the money you made

Will never buy back your soul.

Through folk music, Dylan is allowed to channel his resentment towards corporate leaders into a pacifist, anti-war statement. Like Dylan, Father John Misty uses folk music to condemn those in power. Misty critiques the overtly religious American right and the rapidly rising culture of anti-intellectualism in his 2017 song “Pure Comedy.” Misty critiques the leadership that the religious, anti-intellectual right-wing has elected, asking, “Where did they find these goons they elected to rule them? / What makes these clowns they idolize so remarkable.” Like Dylan, Misty draws on the themes of cowardice and illusion, singing, “Oh comedy, their illusions they have no choice but to believe / Their horizons that just forever recede.” Money is a theme that Misty also parallels, and he sings, “They build fortunes poisoning their offspring / And hand out prizes when someone patents the cure.” Both Dylan and Misty elect to use folk music as a mouthpiece for radical rejection of contemporary politics, but when further contextualized, their similarity seems to end at their shared genre.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, 1963

Pure Comedy, 2017

Simply because Dylan and Misty share a genre does not necessarily mean that the artists share a tone. Dylan opts for a solemn and serious tone while Misty prefers sarcasm and dry humor, reminiscent of the youth culture of their respective time periods. Dylan’s tone throughout “Masters of War” is solemn. Humor does not manifest in any of his verses; Dylan is strictly serious in this song, his voice filled with earnest hatred towards those he considers to be masters of war. Dylan’s chosen words are at times frightening, seen through lyrics like, “For threatening my baby / Unborn and unnamed / You ain’t worth the blood / That runs in your veins.” Even more chillingly, Dylan’s voice rings out:

And I hope that you die

And your death’ll come soon.

I will follow your casket

In the pale afternoon.

And I’ll watch while you’re lowered

Down to your deathbed.

And I’ll stand over your grave

‘Til I’m sure that you’re dead.

The movement against the Cold War was predominantly made up of America’s youth, and they yearned to be taken seriously. Dylan, only in his early twenties when this album was released, was among that youth. He obviously wanted to be taken seriously despite his age, and this is seen in his lyrics; “How much do I know / To talk out of turn / You might say that I’m young / You might say I’m unlearned.” Thus, Dylan’s solemn tone was heavily reflective of youth culture and a desire to be taken seriously.

Bob Dylan took part in many serious protests.

Father John Misty’s tone is the antithesis of Dylan’s, and heavily reflective of modern youth and black-humored internet culture. Seen blatantly throughout his lyrics, and even the title of the song, “Pure Comedy” is riddled with dark comedy and sarcasm. This is not to say that the content of Misty’s song is less urgent than Dylan’s, but rather that Misty utilizes humor to strengthen his criticisms. Misty, for example, criticizes the gender-role dichotomy that is reinforced by the religious right, singing:

Now the miracle of birth leaves a few issues to address

Like, say, that half of us are periodically iron deficient.

So somebody’s got to go kill something while I look after the kids

I’d do it myself, but what, are you going to get this thing its milk?

Humor is once again seen when Misty criticizes the concept of religion, especially because he seeks to prove its ridiculousness:

Oh, their religions are the best.

They worship themselves yet they’re totally obsessed

With risen zombies, celestial virgins, magic tricks, these unbelievable outfits

And they get terribly upset

When you question their sacred texts

Written by woman-hating epileptics.

Father John Misty is known for his humorous dancing and stage presence.

The content featured in both of their songs are reflective of pressing contemporary politics, but their execution of tone renders them opposite artists. Tone proves Dylan and Misty to be separated by time, as they are reflective of vastly different generations of radical political rejection.

Dylan and Misty both draw upon religion to justify their points, but they do this quite inversely. While Dylan condemns corruption and greed using religion as a basis, for Misty, religion itself is the fundamental basis for his criticism. Dylan, raised Jewish and later in life a born-again Christian, concentrated religion in many of his works. Dylan draws upon scripture to condemn corruption, claiming:

Like Judas of old

You lie and deceive.

A world war can be won

You want me to believe.

But I see through your eyes

And I see through your brain.

Like I see through the water

That runs down my drain.

Again, Dylan claims these masters of war to be culprits on the basis of their deviance from moral and devout behavior, singing, “But there’s one thing I know / Though I’m younger than you / That even Jesus would never / Forgive what you do.” Father John Misty is the opposite of Dylan in matters of religion. Raised in an Evangelical household, Misty found religion to be extremely oppressive, and wholeheartedly rejected it in his adulthood. Even his stage name serves to trivialize religion, as he claims it is meant to look “like a Christian puppet show has come to town.” Father John Misty identifies religion as the evil tool that leaders use to gain power in “Pure Comedy.” Misty expounds that humans are selfish, and they use religion to justify evil:

Comedy, now that’s what I call pure comedy.

Just waiting until the part where they start to believe

They’re at the center of everything

And some all-powerful being endowed this horror show with meaning.

Religion is brought up several more times; “Their languages just serve to confuse them / Their confusion somehow makes them more sure,” “These mammals are hell-bent on fashioning new gods / So they can go on being godless animals,” and “And how’s this for irony / Their idea of being free is a prison of beliefs / That they never ever have to leave.” Religion serves as a central theme in each work which, upon first consideration, seems to unite Dylan and Misty. However, through deeper contextualization, Dylan and Misty take vastly different stances on the matter of religion, widening the gap between their artistry, and dispelling the notion that folk can be easily defined.

Bob Dylan became a born again Christian.

Folk music is often generalized, as it is not a mainstream music genre. Labels of conservative, traditional, and simple are often slapped onto American folk music, without any attempt at contextualization. Bob Dylan and Father John Misty, figureheads of American folk music, prove that folk is complicated and is capable of portraying a myriad of perspectives. Both artists prove to be political radicals, defying contemporary politics through the condemnation of corrupt leaders, thus proving that folk music is not necessarily conservative or traditional. Aside from this similarity, the two are actually quite different, electing to use opposite tones and portraying diverging views on religion, thus proving that folk music is not as simple as it is chalked up to be. Folk music, as proven by these icons of the genre, is riddled with complexity, defying the expectation of mainstream music-listeners. Beyond this, folk music is representative of themes that are far from elementary, as proven by Bob Dylan’s revolutionary 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. Dylan was the first musician to ever be awarded this prestigious honor; American folk music has served as a literary mouthpiece in times of political unrest for decades, and is now recognized as so. Perhaps Father John Misty is this generation’s closest attempt at a Dylan figure, and perhaps future Americans will look back at the Trump-era and remember Misty’s quirky rejection of contemporary politics, as we do with Dylan and the 1960s. Time will tell if Misty’s legacy will live up to his childhood idol’s.

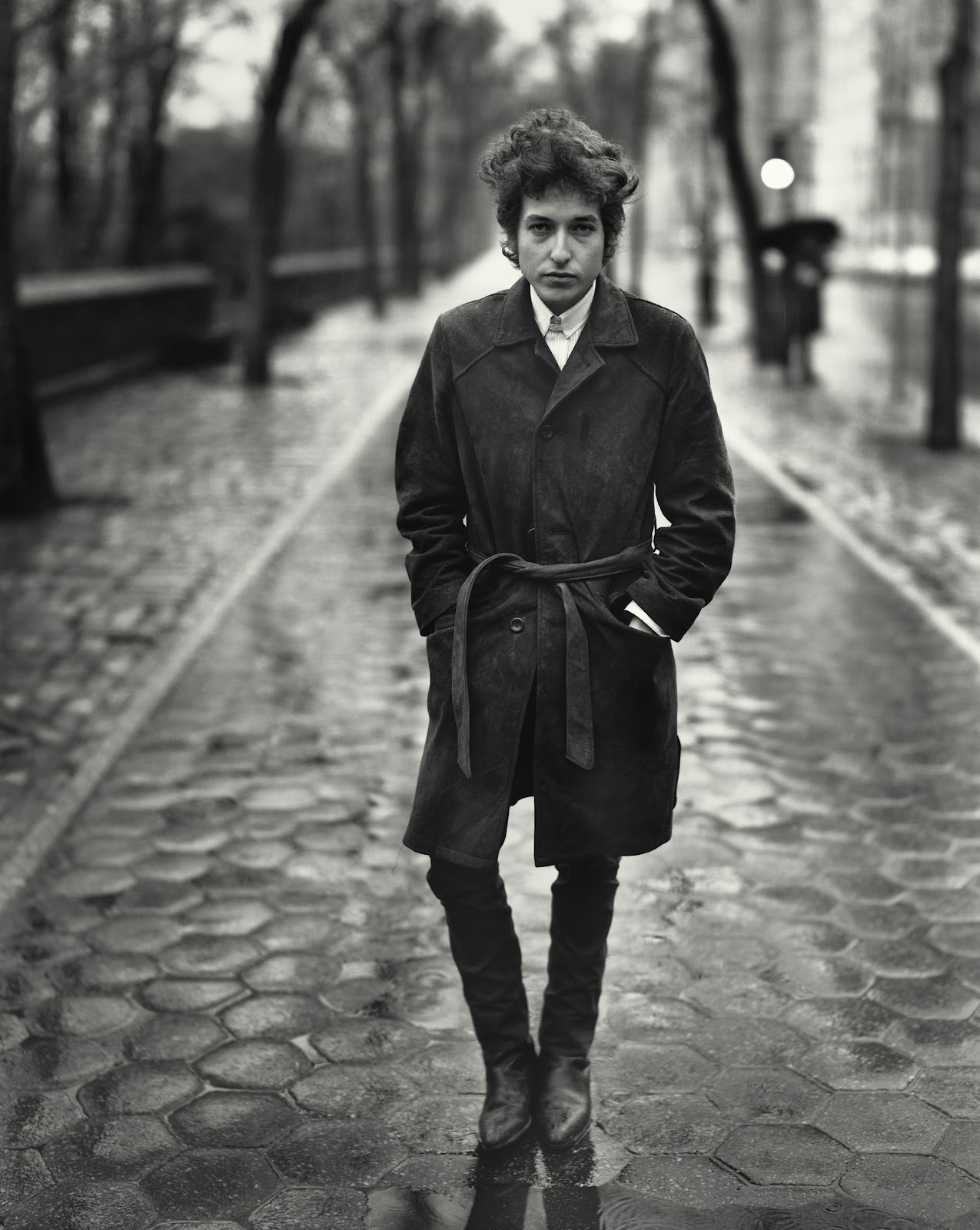

Bob Dylan, 1965. Photograph by Richard Avedon.

Father John Misty.